But where there is limited information there will always be room for argument. Many professionals will not be overly surprised at the ranking of disease clusters, or the categories within each cluster, or the conclusions regarding patient characteristics. This will be in the difference between mental and physical functioning, for instance. Moreover, there are also issues within the quality of life measures that an overall ranking will not highlight.

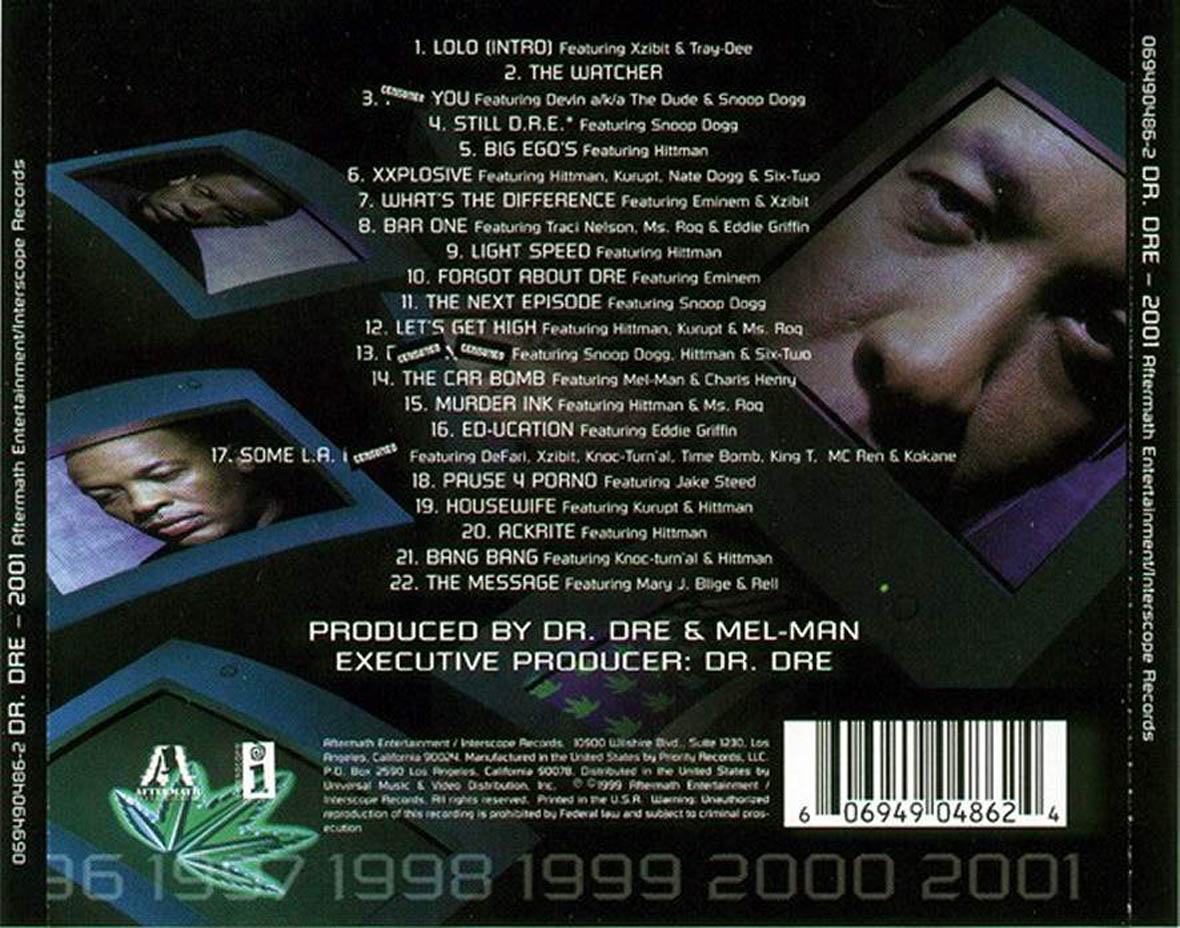

For this analysis, this is with the comparisons across disease categories. So where there is the largest agglomeration of information is where the strongest conclusions lie. There will be limits to how far these sort of data can be subdivided and still give us valid conclusions. Patients who were older, female, had a low level of education, were not living with a partner, and/or had at least one comorbid condition had the poorest quality of life. For psychiatric disorders depression scored worse than anxiety which in turn was worse than alcohol problems. For neurological conditions, Parkinson's disease or epilepsy, multiple sclerosis and stroke scored higher than migraine or neuromuscular disease. For instance, in musculoskeletal conditions, ostoeoathritis had more adverse impact than back impairments, which scored higher (worse) than rheumatoid arthritis. Higher scores imply poorer quality of life Musculoskeletal conditions, renal disease, cerebrovascular/neurological conditions and gastrointestinal conditions impacted most severely on quality of life.įigure: Summed rank scores for disease clusters. The summed rank scores for chronic disease clusters are shown in the Figure. This summed rank produces low scores for the diseases or disease clusters causing the least distress, and high scores for those causing the most problems. This was done for all quality of life domains, and the ranks for individual domains added together. Thus if three diseases scored (say) 5, 10, and 15 (with 5 the 'best' score), then they would be ranked 1, 2 and 3. The method used was the ranking of mean scores.

2001 the chronic full#

Studies had to use a standardised quality of life instrument, have full coverage of quality of life domains, include a range of chronic diseases, be big (at least 200 patients), have medically confirmed diagnoses, be obtained since 1992 and be geographically broad.Įight data sets broadly fulfilling these categories were obtained, with information on about 15,000 people. This is definitely a two-brains paper, but worth conquering.Īll research groups known to examine chronic diseases in the Netherlands were contacted to see what data sets were available.

A study with about 15,000 patients from Holland gives us just this. Even then there may be problems in interpretation, but it might provide some better insights into disease impact on people. What is needed is surveys using the same instrument to measure quality of life, used in large enough samples of patients, with a similar range of disease severity, and with a similar demographic base. Anecdote piles upon anecdote, but the problem is that the plural of anecdote is not data. The question of which chronic disease most impacts upon quality of life can lighten many a dreary hour. Study Results Disease clusters Disease categories Patient characteristics Comment The man on the stair

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)